As we saw in the last posting, ask Tory politicians what the "Big Society" is, and you are likely to get as many different answers as there are politicians. (If they are being very honest, they may even tell you that they don't believe in it themselves, and the Tory press and blogosphere has been equally sceptical.) In many respects, attempts at defining the "Big Society" has been hugely problematic for the government. Phillip Blond, author of the book "Red Tory" and a "guru" of the ‘Big Society’, has become deeply unhappy with whole project, complaining that the Government is ‘losing itsexpressed concern:

As we saw in the last posting, ask Tory politicians what the "Big Society" is, and you are likely to get as many different answers as there are politicians. (If they are being very honest, they may even tell you that they don't believe in it themselves, and the Tory press and blogosphere has been equally sceptical.) In many respects, attempts at defining the "Big Society" has been hugely problematic for the government. Phillip Blond, author of the book "Red Tory" and a "guru" of the ‘Big Society’, has become deeply unhappy with whole project, complaining that the Government is ‘losing itsexpressed concern:“We know the Big Society narrative was very badly communicated … it was insufficiently thought through, and… people now think of it as just volunteering and philanthropy - which is a disaster.”

On other hand some Big Society "purists" would argue it should not be defined at all - that each community must work out what it means for them. Lord Nat Wei, the "Big Society Tsar" tried to sum it up succinctly. The Big Society is, he said, defined by 3 characteristics:

1. The needs of different places are dealt with in different ways

2. It lets people take control

3. It leads to similar senses of community arising in inner-city and rural areas that weren't there before. (Apparently the surburbs are far more likely to have the Big Society in operation)

|

| Lord Wei |

So the Big Society was to be about empowerment for communities; public services being delivered in different ways - possibly by voluntary groups or social enterprises; "localism & decentralisation" - local communities deciding what is best for them without government interference; and a greater sense of mutual responsibility and community brought about by an increase in altruistic volunteering and philanthropic giving from individuals and companies.

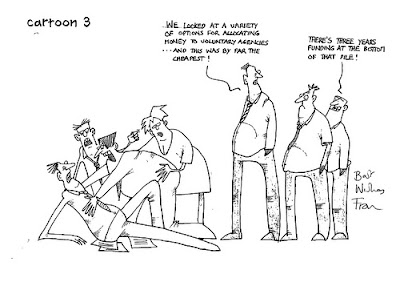

Lofty and laudible aims perhaps, but to the sceptics the Big Society was a cynical attempt by Cameron to decontaminate the "toxic" brand of Conservatives as the "nasty party", or was a cover for deep and prolonged cuts that would shift blame from the government to the communities themselves. If your community lacked facilities and infrastructure now, it would not be the government's fault, but yours. Your community was simply not motivated and / or organised enough.

In some respects, the idea of communities solving their own problems may be appealing - as may be the idea that community assets might transfer to citizen-led organisations - creating a greater sense of community pride, and costing the public purse less. However, let's examine how that might happen. Let's think about two communities:

.jpg) The first is a community where skills are lower than average, has lower levels of academic achievement, unemployment is higher, and those in work are often in low-wage jobs, meaning people work long hours or hold several jobs to make ends meet. Many are in rented housing, meaning the community has a high "churn" - people may not stay for long. The estate has a higher proportion of people for whom English is second language, single-parent households, and those on disability benefits.

The first is a community where skills are lower than average, has lower levels of academic achievement, unemployment is higher, and those in work are often in low-wage jobs, meaning people work long hours or hold several jobs to make ends meet. Many are in rented housing, meaning the community has a high "churn" - people may not stay for long. The estate has a higher proportion of people for whom English is second language, single-parent households, and those on disability benefits. The second community is made up of mostly privately-owned homes, meaning people are largely more "rooted" in the community. The population is made up of people from professional backgrounds - business people, solicitors, academics. A good proportion are retired, financially independent and with time on their hands. They are well-networked, and have influence.

The second community is made up of mostly privately-owned homes, meaning people are largely more "rooted" in the community. The population is made up of people from professional backgrounds - business people, solicitors, academics. A good proportion are retired, financially independent and with time on their hands. They are well-networked, and have influence.

The two communities' libraries are under threat from the local authority cuts, but the council has pointed out that they might want to think about running the libraries themselves under the new "localism" and "opening public services" agendas. The communities think about taking on the buildings as community assets, and using volunteers to staff them. Can you see the problem?

The second community will be motivated and mobilise. People know each other, and have a long-term shared commitment to their neighbourhood. Many in the first community do not know if they will still live there when their tenancy ends - and in many cases that tenancy may only be 6 or 12 months in total.

The second community will develop a business plan, and will pull on its professional and social networks to secure pro bono services to transfer the asset. Legal advice, conveyancing services, insurance services, surveying are all accessed with relative ease. Detailed funding applications are made to social financiers, and fundraising networks appeal to well-heeled residents. The first community is advised about all it will need, and begins to cost out the same professional services. Already the scale of the task seems colossal, and many are feeling demotivated. The people on the estate have little or no spare money to invest themselves, and funding applications, without support, are badly worded or structured and are regularly rejected in the competitive world of grant funding. Social finance is hard to access as the people in the community have often had a bad experience with credit.

The second community will develop a business plan, and will pull on its professional and social networks to secure pro bono services to transfer the asset. Legal advice, conveyancing services, insurance services, surveying are all accessed with relative ease. Detailed funding applications are made to social financiers, and fundraising networks appeal to well-heeled residents. The first community is advised about all it will need, and begins to cost out the same professional services. Already the scale of the task seems colossal, and many are feeling demotivated. The people on the estate have little or no spare money to invest themselves, and funding applications, without support, are badly worded or structured and are regularly rejected in the competitive world of grant funding. Social finance is hard to access as the people in the community have often had a bad experience with credit..jpg) The second community has people with time on their hands - the wealthy retired, and people who are able to stay at home, or work part-time, because their partner's income is more than sufficient. These people are able and willing to give their time to the library project, and their level of skills, education and social skills mean that they can quickly grasp what is required of them and complete their tasks ably. The first community has people who have to work in several jobs to make ends meet. They are carers, casual labourers, shop staff. They do not know from one week to the next what their shifts and working hours will be, making it very difficult to commit with any certainty to being at the library at specific times. When they are able to make it, the job itself may feel very new and intimidating without extensive training.

The second community has people with time on their hands - the wealthy retired, and people who are able to stay at home, or work part-time, because their partner's income is more than sufficient. These people are able and willing to give their time to the library project, and their level of skills, education and social skills mean that they can quickly grasp what is required of them and complete their tasks ably. The first community has people who have to work in several jobs to make ends meet. They are carers, casual labourers, shop staff. They do not know from one week to the next what their shifts and working hours will be, making it very difficult to commit with any certainty to being at the library at specific times. When they are able to make it, the job itself may feel very new and intimidating without extensive training.

And so it goes on. The communities do not start from an equal place, and in the "go and do it" world of Big Society those already most resilient and well equipped are most likely to succeed. That is where infrastructure services (like Exeter CVS) come in. In our community development capacity we can work with communities and fledgling projects to help them, support them, train them. The government might point towards investment such as the £400k Exeter CVS recently won from the Transforming Local Infrastructure Fund as an example of their adding capacity to the sector. But there's a catch. This money is designed to streamline services and maximise efficiency. Nothing wrong with that, of course, but the ultimate aim is for infrastructure "to be less reliant on state funding." Put another way, to be in a position to charge for our services. So our communities would pay us as a professional service.

The problem is, as we have seen, that communities like "community 1" in the example above does not start with any money. Later this year, the government is proposing a fund that would see communities bidding for grants in order to buy in infrastructure services. This may seem fair enough at first glance (if a somewhat convoluted way of funding!) , but we are back to the issue that without support to start with, some communities will be in a better position to bid than others....

As someone said to me recently, "The Big Society is turning into the Everyone-for-Themselves Society where the strongest communities grow stronger still, and the poorest areas decline still further."

The problem is, as we have seen, that communities like "community 1" in the example above does not start with any money. Later this year, the government is proposing a fund that would see communities bidding for grants in order to buy in infrastructure services. This may seem fair enough at first glance (if a somewhat convoluted way of funding!) , but we are back to the issue that without support to start with, some communities will be in a better position to bid than others....

As someone said to me recently, "The Big Society is turning into the Everyone-for-Themselves Society where the strongest communities grow stronger still, and the poorest areas decline still further."

No comments:

Post a Comment